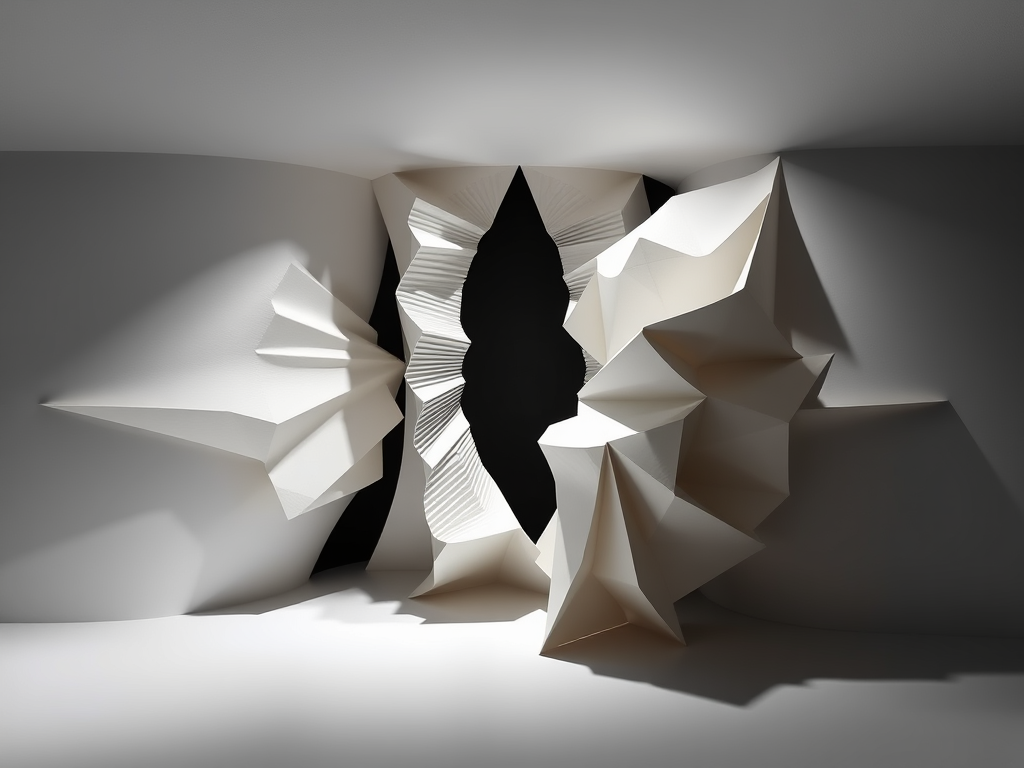

Now that the Mona Hatoum exhibition has closed, I’ve found myself thinking about it more, not less —: rooms shaped by tension rather than comfort, everyday materials made strange or quietly threatening.

Hatoum’s work doesn’t invite interpretation so much as awareness. You don’t stand outside it and understand; you’re implicated.

That quality feels significant when thinking about illness — and particularly degenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s. In dementia, experience often becomes fragmented: perception shifts and familiar spaces can feel suddenly unreliable. Hatoum’s work seems to mirror that instability without trying to explain or correct it.

What struck me most in conversations afterwards was how the work seemed to hold space rather than offer answers. There is no narrative of recovery, no reassurance offered. That feels ethically important.

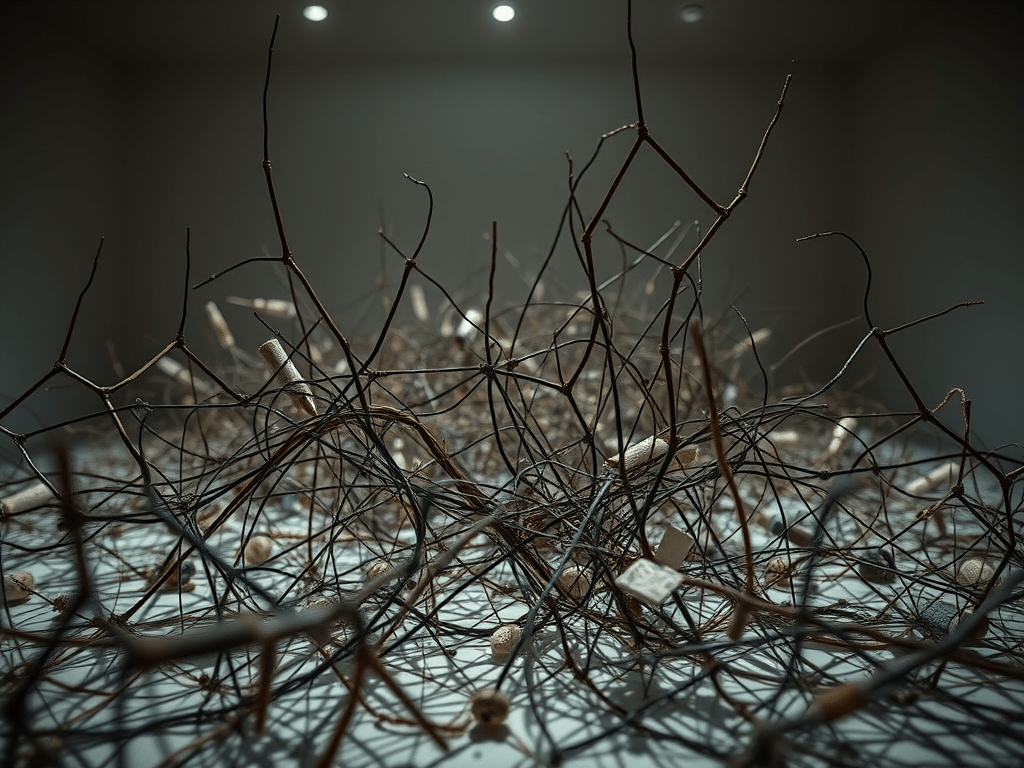

In that sense, Hatoum’s practice resonates strongly with ideas from medical humanities and dementia ethics: a refusal to reduce experience to diagnosis. Instead, the work asks us to remain with uncertainty — to recognise that dignity and meaning don’t depend on cure.

In healthcare, data, and policy, we are trained to resolve, predict, and stabilise. But degenerative illness reminds us that not everything can be fixed — and not everything should be framed as failure.

Not all care is about solutions.

Some of it is about staying.

TLDR: Sometimes the ethical task is simply to witness and to resist the urge to tidy complexity away.

Leave a comment